An Introduction to Dollar-Cost Averaging

While dollar-cost averaging might not result in higher returns on average, it may improve one’s investment experience.

At one time or another, you may find yourself holding a sizable cash balance and wonder how to go about investing it. Life events that may lead to such a scenario include the sale of a business, receiving an inheritance, or the award of a large bonus.

When faced with the prospect of investing a sizable cash position, investors are often afraid of committing new capital to equity markets at precisely the wrong time—right before a significant downturn. For this reason, investors may wait for the next market correction before adding exposure to their equity holdings. But history shows that market runs can carry on for extended periods, potentially resulting in lost opportunities for those retaining excess cash.

An alternative to investing a lump sum all at once—be it immediately or in the future after a downturn—is to invest capital incrementally over time according to a predefined schedule. The latter approach is known as dollar-cost averaging (DCA) and serves as a useful tool for helping investors overcome debilitating emotions such as fear and regret.

What Is Dollar-Cost Averaging?

Dollar-cost averaging is employed when an investor purchases a set dollar amount of a security, or group of securities, on a consistent interval—generally monthly or quarterly—over a predefined period (generally less than one year).

For example, an individual with $120,000 of excess cash to invest could employ a dollar-cost averaging strategy by purchasing $10,000 of a U.S. equity fund every month for twelve months, rather than investing it all right away or waiting to invest it all at some unknown date in the future after a market downturn.

When Is Dollar-Cost Averaging Appropriate?

Standard financial analysis shows that dollar-cost averaging, more often than not, results in a lower ending portfolio value than lump-sum investing. This should not come as a major surprise since capital markets trend upward over time, most of the time. So, dollar-cost averaging should not be thought of as a tool for increasing the expected rate of return of a portfolio.

So, why do it? By staggering securities purchases over time, dollar-cost averaging can help investors with excess cash overcome the fear of investing just before a downturn (which may or may not happen for some time) and minimize feelings of regret should a downturn materialize.

Because fear and regret are powerful emotions that can lead to poor decision-making in the future, employing a strategy that seeks to minimize these emotions can make a lot of sense, even if it’s not economically optimal. In other words, while dollar-cost averaging might not result in higher returns on average, it may improve one’s investment experience.

What to Expect When Dollar-Cost Averaging

Prior to implementing a DCA program, it is important to calibrate expectations. A wide range of results may be experienced when implementing a DCA program (relative to a lump-sum investment) based on the timing and magnitude of market movements.

To illustrate, we model four hypothetical dollar-cost averaging scenarios using stock market data from the 2008 global financial crisis and the subsequent recovery. In each example, we compare outcomes of a $100 monthly investment for twelve months versus a lump-sum investment of $1,200. The only variable that changes between each scenario is the start date.

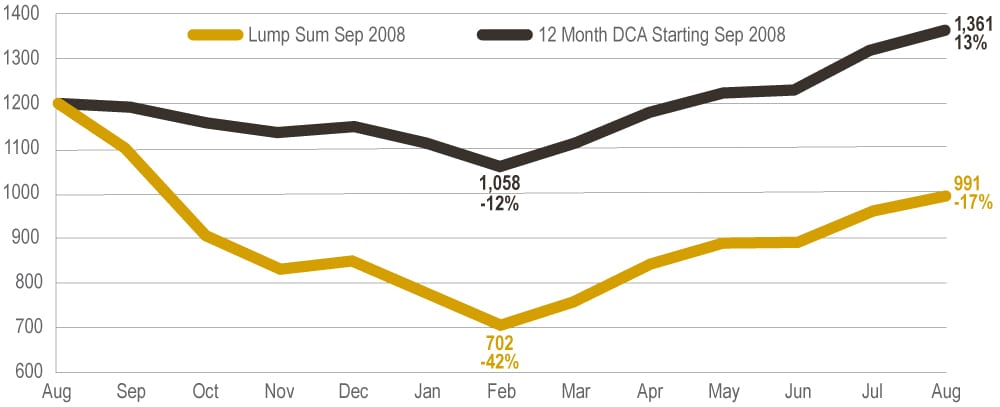

Scenario 1: Stock Market Declines as Credit Crisis Spreads

Scenario 1 models a DCA program initiated in September 2008 at the height of the financial crisis. With equity markets in freefall, this scenario represents an ideal outcome for a DCA program relative to lump-sum investing. By investing new capital incrementally, the dollar-cost averaging investor avoided much of the drawdown. But, by continuing to buy into equities as the decline accelerated, the DCA investor quickly recouped moderate losses and ended the twelve-month period with a 13 percent gain relative to a 17 percent loss for the lump sum alternative.

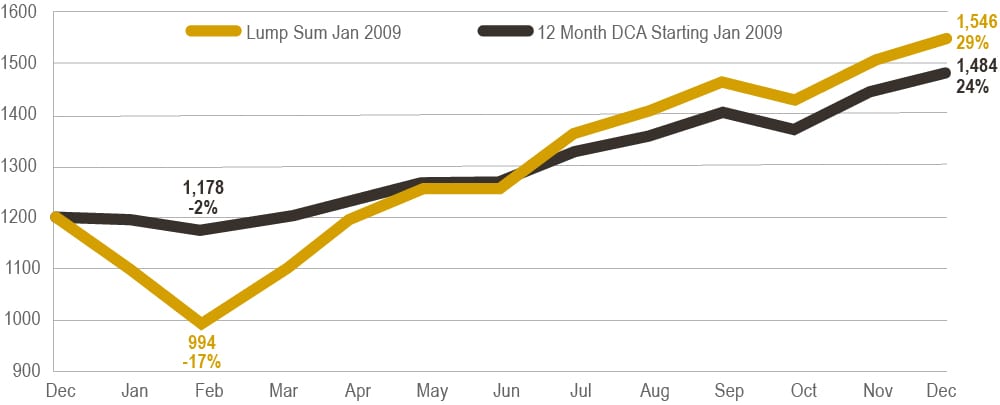

Scenario 2: Stock Market Briefly Declines and Recovers Sharply

Scenario 2 models a DCA program initiated in January 2009, three months after the start of the DCA program modeled in Scenario 1, and three months before equity markets bottomed out and began to recover from losses sustained during the financial crisis.

By investing new capital incrementally, the dollar-cost averaging investor largely avoided the initial decline. But, with equity markets recovering sharply, the lump-sum investor eventually caught up with the DCA investor, while eking out a marginal victory from start to finish.

Despite earning slightly higher returns via the lump sum alternative, it can be argued that the DCA program offered a superior “experience,” having largely avoided the 17 percent decline at the start of the period while capturing most of the upside gain through the end of the period.

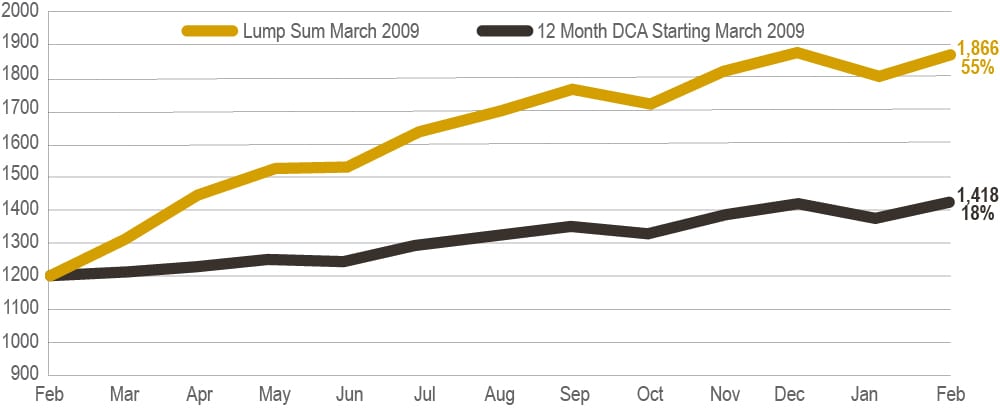

Scenario 3: Stock Market Recovers Sharply

Scenario 3 models a DCA program initiated in March 2009, three months after the start of Scenario 2, as equity markets began to recover from losses sustained during the financial crisis. With equity markets experiencing a sharp and steady appreciation, this scenario represents the least appealing outcome for a DCA program relative to immediate lump-sum investing.

By investing new capital incrementally, the investor missed out on a considerable portion of the gains achieved during the analysis period. That said, the DCA program could have offered an improvement relative to a “wait and see” investor who remained on the sidelines.

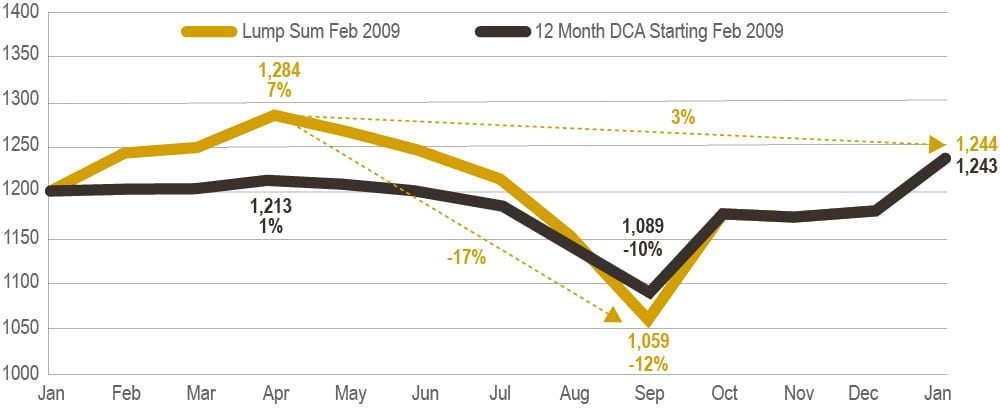

Scenario 4: Before, During, and After U.S. Credit Rating Downgrade

Scenario 4 models a DCA program starting February 2011, with the full analysis period including market performance before, during, and after the U.S. credit rating downgrade.

From start to finish, the DCA and lump-sum options achieved identical performance. But, the experience of the dollar-cost averaging investor is arguably inferior to that of the lump-sum investor. Why? When markets start on an upward trajectory and then decline, DCA investors are often dissatisfied that their portfolio caught minimal gain on the initial upward move and a meaningful portion of the subsequent move downward. It can take some convincing that such a relationship is unlikely to persist with a fully invested portfolio.

Best Practices and Considerations for Dollar Cost-Averaging

Dollar-cost averaging is not something that can be done correctly, per se. Instead, it is an exercise in thoughtfully investing capital in a way that manages human emotions, namely fear and regret. While there is no perfect answer as to how long one should take to deploy excess cash, there are basic guidelines to consider:

- The more volatile the asset class, the longer you might want to average into positions. Within the context of a Brighton Jones portfolio, we consider the following DCA time frames for strategies within each portfolio component:

- Capital Preservation (low volatility): 1-2 months

- High Income (moderate volatility): 2-3 months

- Global Equity (high volatility): 3-12 months

- Recent performance can be factored into the length of a DCA period.

- If equity markets are trading near highs and have been trending upward for an extended period, investors may want to spread purchases out over a longer period, say 8-12 months.

- If equity markets are in the midst of a pullback, correction, or bear market, investors may want to accelerate purchases to take place within a 3-8 month window.

- There is no set rule that DCA purchases have to be made in equal installments. Investors may consider front-loading purchases of asset classes that suffered recent declines.

- Not every asset class, even within the global equity portfolio, needs to be on the same schedule.

- Many investors are aware that domestic equities are trading near all-time highs with above average price-to-earnings ratios. But, foreign developed and emerging markets have trailed their domestic counterparts throughout the current expansion. As such, investors might average into foreign strategies over a shorter period than domestic strategies.

Sample Schedule

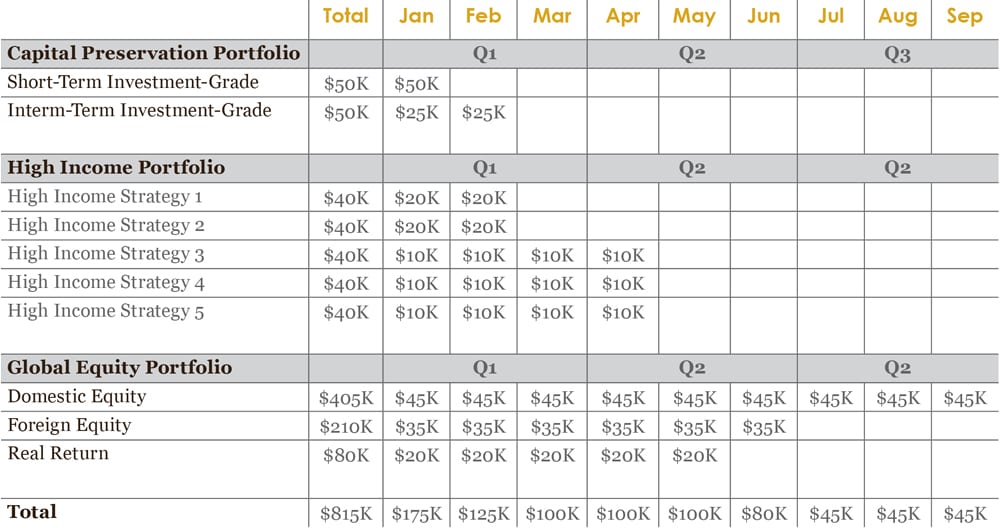

At the onset of a DCA program, it is helpful to map out purchases of specific securities by month, using a table similar to the one provided below. Putting a plan on paper increases the chances you stick to it!

Dollar-Cost Averaging in Perspective

The validity of dollar-cost averaging is based on the notion that it is emotionally preferable to be approximately right than precisely wrong. While dollar-cost averaging may not result in higher expected returns, it can offer peace of mind to those who fear making decisions that could result in an unlucky outcome, and it can alleviate the regret that overcomes us when unlucky outcomes materialize.

It is important to reiterate that dollar-cost averaging is not something that can be done correctly per se; rather, it is something that can be done thoughtfully. The right approach for one person may not be the right approach for another.

At Brighton Jones, we work with clients to customize dollar-cost average strategies that consider both personal factors and market conditions.

Read more from our blog: