Should Bondholders Be Afraid of Rising Interest Rates?

Interest Rates and Bonds

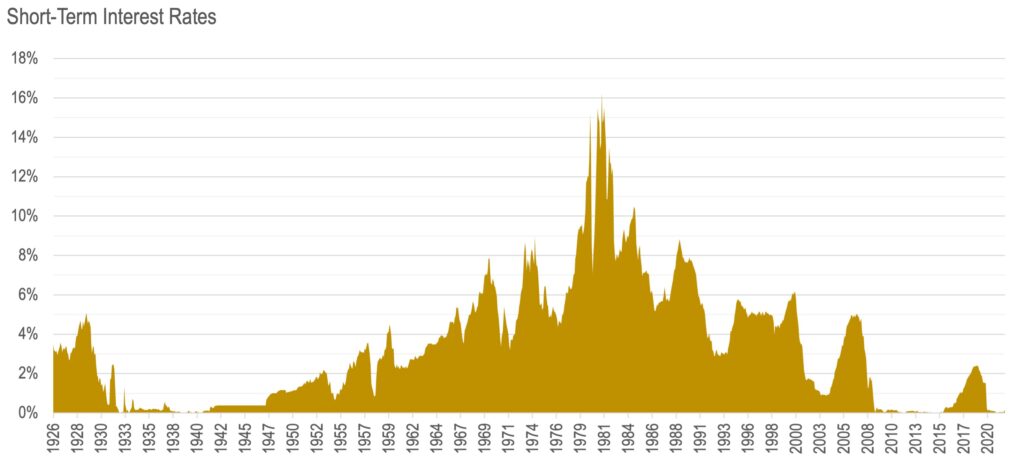

In 1981, the interest rate on 3-month U.S. Treasury bills peaked at an all-time high of 16.3 percent. Since that time, interest rates on T-bills have trended lower, eventually bottoming out at an all-time low of 0.01 percent in 2011.

Source: Federal Reserve of St. Louis, Brighton Jones

In an introductory course to finance, one of the first things we learn about fixed-income securities is that bond prices vary inversely with interest rates. That is, bond prices go down when interest rates go up, and vice versa.

Because interest rates have been in a state of decline since 1981, many observers refer to the past four decades as a bull market for bonds.

And, in observing that interest rates remain near all-time lows (with only one direction to go), many fear that the future will bring about a secular bear market in bonds.

And, in observing that interest rates remain near all-time lows (with only one direction to go), many fear that the future will bring about a secular bear market in bonds.

Indeed, some market observers have been issuing warnings of an imminent bond market implosion since the Federal Reserve and other central banks slashed interest rates during the 2008 global financial crisis.

But, when it comes to investing, simplified rules of thumb (e.g., sell bonds when interest rates are about to rise) are unlikely to yield superior long-term investment results. A look at the mechanics of fixed-income securities will dispel the misconception that well-diversified bond investors should fear rising interest rates.

Should I Hold or Sell Bonds When Interest Rates Rise?

Airline pilots spend hours and hours in flight simulators, navigating through simulated storms and other unusual crises. This training ensures pilots will be well-prepared to remain calm and rational when faced with difficult situations in real life.

Similarly, the more we know about how securities markets have behaved in the past, the more we will understand their true nature and how they might behave in the future. Such an understanding enables us to act rationally and hold our bond portfolios when other market participants might panic and sell.

With some market observers predicting a prolonged period of losses in the bond market (due to the prospect of rising interest rates), our first inclination is to look back in time to see if we have previously encountered a similar fact pattern to the current bond market.

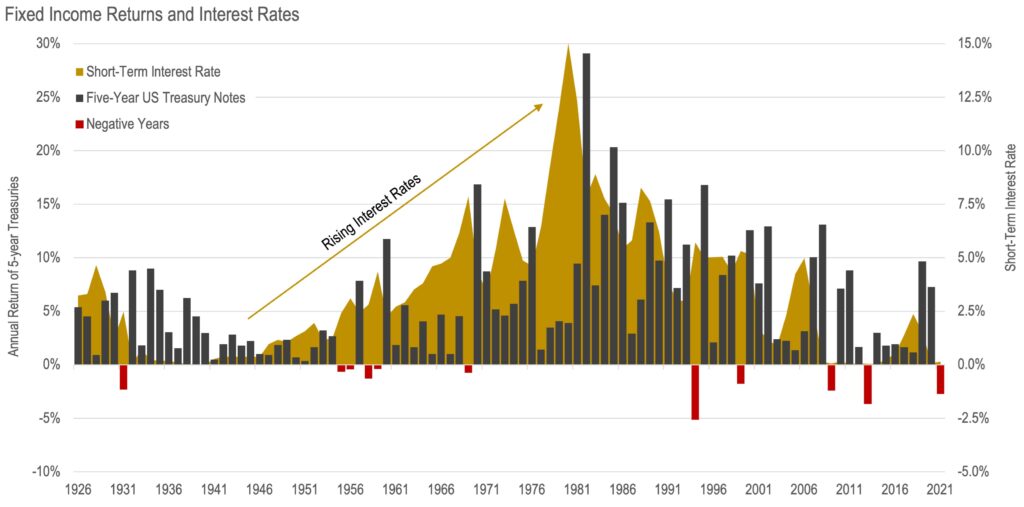

In the chart below, we plot the calendar year returns of the 5-year U.S. Treasury Bond Index (bar chart, left axis) against short-term interest rates (area chart, right axis). As you can see, interest rates previously rose from near-zero to the mid-teens from the early 1940s to the early 1980s, yet bond returns were mostly positive in these years. And, when returns were negative on a calendar year basis, the magnitude of the losses in fixed-income securities was relatively insignificant (notice the scale of the left axis) and certainly not comparable to equity market volatility.

Source: Federal Reserve of St. Louis, Dimensional Returns 2.0, Brighton Jones

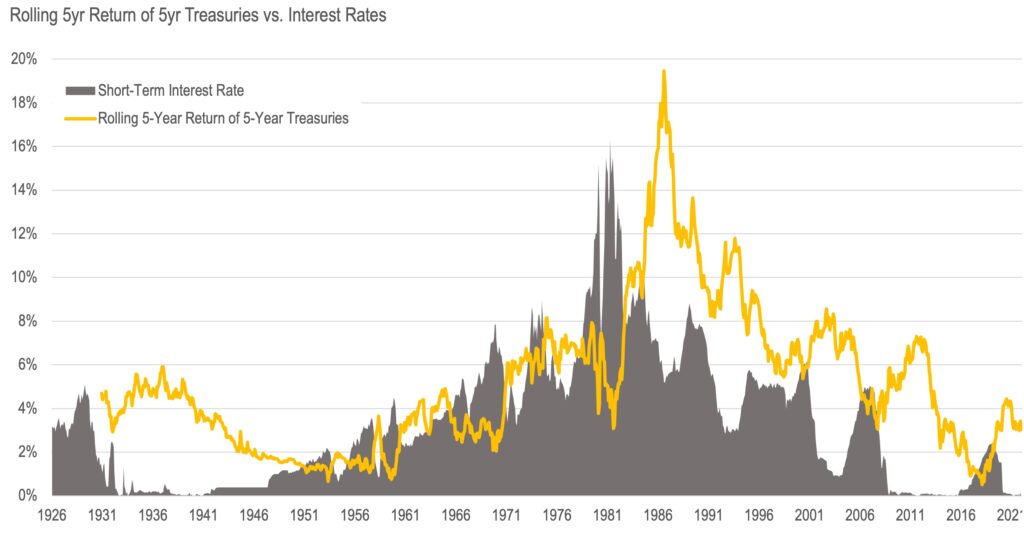

Indeed, the data does not suggest that investors in shorter-term, high-quality fixed-income securities should fear rising interest rates. In fact, when we plot the 5-year rolling return of the 5-year U.S. Treasury Bond Index (below), we see evidence of the opposite—fixed-income returns trended higher over time as interest rates rose and trended lower as interest rates declined.

Source: Federal Reserve of St. Louis, Dimensional Returns 2.0, Brighton Jones

Bonds Tend to Produce Positive Cash Flow Over the Long Term

Now, simply observing that fixed-income returns were stable during prior periods of rising interest rates is not enough evidence to throw out the notion that bond investors should fear rising interest rates. To gain confidence that the future is likely to resemble the past, we must explore why fixed-income securities provided stable returns throughout prior periods of rising interest rates.

Bonds are a contractual obligation of an entity that promises to pay specified sums of money on specified future dates. Barring default, investors holding fixed-income securities know the precise timing and amounts of future cash flows. This makes it easy for us to model how we should expect bonds to respond (both initially and over time) to rising and falling interest rates.

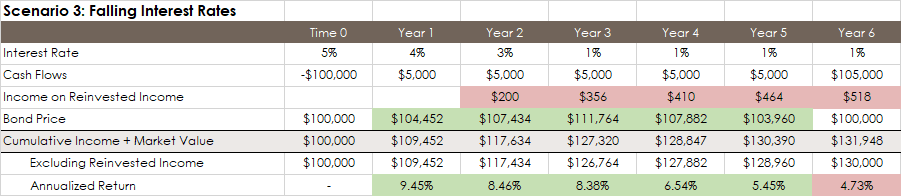

Below, we outline three scenarios to illustrate how bonds work. The three scenarios model how cash flows, bond prices, and wealth accumulation are impacted—both initially and over time—when interest rates (1) remain constant, (2) when they rise, and (3) when they fall.

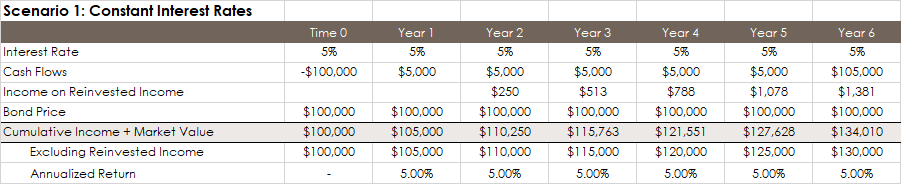

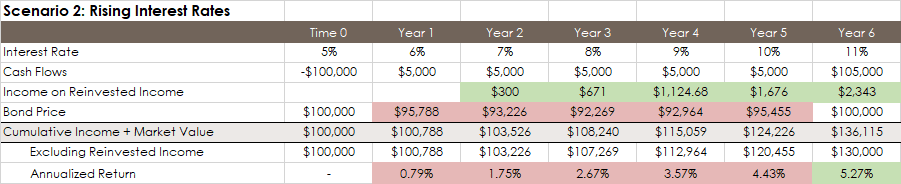

In each scenario, we assume an investor purchases a bond for $100,000 with an interest rate of 5 percent. At Time 0, the investor will have a negative cash flow of $100,000, but will take ownership of a bond worth the equivalent amount. In each of the next six years, the investor will receive $5,000 in interest payments in addition to receiving the $100,000 par value back in the final year. We further assume the investor takes each interest payment and reinvests in new bonds at the prevailing interest rate. In the tables, we calculate the growth of wealth as the cumulative income earned plus the current market value of the bond.

- To understand what occurs when interest rates rise or fall, we must first observe what happens when interest rates remain unchanged.

- In scenarios 2 and 3, we highlight what has changed relative to scenario 1.

- As interest rates increased, the price of the bond initially fell below its par value of $100,000.

- When the bond matured in year 6, the investor received its par value of $100,000 back, despite the value falling to as low as $92,269 in year 3.

- Even though the bond price declined in value by $7,731 by year 3, the investor still had a positive total return, having earned $15,000 in cumulative interest payments plus $971 of income on reinvested income up to this point.

- As interest rates increased, the investor received more income on reinvested income relative to the base case scenario.

- By the end of year 6, the investor earned a higher return (5.27 percent) than the starting yield (5 percent) as income was reinvested at progressively higher rates.

- As interest rates decreased, the price of the bond initially rose above its par value of $100,000.

- When the bond matured in year 6, the investor received its par value of $100,000 back, despite the value rising to as high as $111,764 in year 3.

- As interest rates decreased, the investor received less income on reinvested income relative to the base case scenario.

- By the end of year 6, the investor earned a lower return (4.73 percent) than the starting yield (5 percent) as income was reinvested at progressively lower rates.

Key Takeaways

- In all three scenarios, the cumulative income plus market value in year 6 (excluding income on reinvested income) was $130,000 regardless of interest rate movements. This is because fixed-income cash flows are contractual, with the timing and amounts specified in advance. The only uncertain variable is the future interest rate at which cash flows will be reinvested.

- Taking into account interest earned on reinvested income, the investor yielded the highest return and had the highest terminal wealth value in the rising interest rate scenario (because income was reinvested at progressively higher rates).

- Because we know the timing and amounts of future cash flows for fixed-income securities, we can reliably model how bonds might respond to rising and falling interest rates. The hypothetical examples above demonstrate why bond returns trended higher (lower) over time during prior periods of rising (falling) interest rates (in our historical dataset).

Conclusion

While some market observers have been issuing warnings of a secular bear market in bonds since the height of the 2008 financial crisis, history and reason suggest that a well-diversified bond portfolio will ultimately benefit over time from higher interest rates. This is not to say that bond returns will be positive every month, quarter, or year (just as equity returns will not be positive every month, quarter, or year); but we continue to expect that investors in fixed-income securities will be rewarded with positive returns in the future (over time), just as they have in the past (even as the Federal Reserve normalizes its interest rate policy).

This article was originally published on April 12, 2018. It has been updated.