In the Wake of Silicon Valley Bank’s Collapse: FAQs and Commentary

Given the events unfolding with Silicon Valley Bank, along with the banking sector more broadly, we want to share our responses to frequently asked questions from clients along with additional updates and context. While there is no shortage of commentary from the media, we aim to provide abbreviated responses while filtering out the most nuanced details. In other words, we want to inform you about what’s going on in a way that doesn’t require you to be a banking expert. Should you have any questions or concerns, please do not hesitate to reach out to your planning team.

What happened at Silicon Valley Bank?

All banks are exposed to what’s called “Asset Liability Mismatch.” Bank liabilities are customer deposits that can be withdrawn on demand, and bank assets are typically longer-term loans or securities that might be illiquid or fluctuate in value. Banks will invest in longer-term loans or securities in order to generate income to pay depositors some amount of interest while earning a profit on the spread (called the net interest margin). Banks do not invest all customer deposits in longer-term loans and securities, however; they do aim to maintain ample liquidity to meet potential customer withdrawals.

The problem at Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) stemmed from having a homogenous customer base largely consisting of venture capital-backed companies and start-ups. With public and private equity markets coming under pressure over the past year, many of these firms have opted to spend their existing cash instead of attempting to raise new capital at lower valuations. The level of withdrawals among SVB’s client base exceeded expectations, forcing the bank to sell some of its longer-term fixed income holdings at a loss. This spooked investors and depositors alike, leading to an even larger wave of withdrawals. It was reported by Bloomberg that $42 billion, representing more than 20% of deposits, was withdrawn from the bank last Thursday alone. By comparison, $16.5 billion was withdrawn over the 10-day period leading up to the bankruptcy filing of Washington Mutual in 2008.

As if having a homogenous client base wasn’t problematic enough on its own, a handful of high-profile venture capital firms advised their portfolio companies to withdrawal their cash from the bank. If a single venture capital firm advises several hundred companies to move deposits to a different bank—and those companies follow that advice—imagine the damage even a small handful could do. That’s what happened. While Silicon Valley Bank could have better managed its asset liability mismatch, it’s failure was probably avoidable. In short, the venture capital industry failed the prisoner’s dilemma test.

What is the government doing?

On Sunday evening, the FDIC, Federal Reserve, and US Treasury jointly announced a plan to guarantee deposits of all sizes in an effort to stem contagion risk. Additionally, the Federal Reserve will create a new loan facility (Bank Term Funding Program) aimed at safeguarding other institutions affected by market instability. The loan facility will allow banks to borrow directly from the Federal Reserve for a one-year term in exchange for pledging the par value of their treasury and agency debt as collateral. The cost of the program will be borne by all banks so that taxpayers are not on the hook for any costs associated with the various measures.

It is worth pointing out the nuance that the government is allowing banks to fail, while fully protecting customer deposits. This means Silicon Valley Bank is gone, its executives and employees will lose their jobs, and shareholders will be wiped out. But businesses and individuals with large cash balances need not worry about the safety of their deposits at Silicon Valley Bank or elsewhere.

The announcement of these measures was met with a strong positive reaction in futures markets, but the initial gains vanished before the market opened Monday morning. With one final market check before going to print, equity markets are making a break higher once again (after a couple fits and starts throughout the morning). A reasonable assumption is that the market at large views these measures as appropriate and sufficient, but hedge funds are potentially causing large intraday volatility. In 2008, regulators temporarily banned short selling of banks. A similar action may need to be considered once again.

Should we be concerned that a financial crisis similar to 2008 is unfolding?

The situation is fluid and fast-moving with new developments emerging by the minute. Based on what we know up to this point in time, there are a number of key differences between the 2008 financial crisis and what is taking place today. Here is an abbreviated overview:

Leading up to the 2008 financial crisis, many banks originated a lot of interest-only adjustable-rate mortgages to borrowers with low credit quality (or no credit history) and often with loose income verification. Borrowers favored these types of loans, operating with the expectation that they would be able to refinance before the amortization period began, often times cashing out equity from continued home price appreciation. When market conditions didn’t allow these borrowers to refinance, they were no longer able to make loan payments, and banks were left holding non-performing mortgages that nobody else wanted to buy (which is when the Federal Reserve stepped in to buy them).

Today, banks are not holding these types of low-quality mortgages—they are holding US Treasuries and higher quality mortgages backed by the US government. But, because some banks extended the maturities of their Treasury/mortgage holdings, they are having to sell them at a loss (the result of larger than expected interest rate hikes) in order to meet customer withdrawals that turned out to be higher than expected.

With equity markets panicking, interest rates have plummeted. In turn, this may help improve bank balance sheets as treasury prices have soared. Hence, the current problem (which is a severe duration mismatch) may benefit from a self-correcting or self-stabilizing mechanism if yields drop, giving banks an opportunity to lower their duration profile by selling some of their long-term bonds at now higher prices. This is different than a self-reinforcing breakdown in credit quality, where losses to one beget losses to others, which we experienced in 2008.

An interesting parallel

It is worth taking this opportunity to draw the connection between what we described earlier as the problem of “asset liability mismatch” to how we manage money for clients. Our investment process begins with the belief that that the key to assuming risk responsibly in pursuit of investment returns is to give each market segment an adequate amount of time to achieve its expected return. To do this, our Cash Needs Analysis computes a running total of annual cash needs, and we then assign holding period targets for every investment in our portfolio (with more volatile market segments being given more time to deliver the desired outcome). So, what went wrong with Silicon Valley Bank? They didn’t do a good job of stress testing their potential cash needs (withdrawals minus deposits) and were forced to sell long-term assets at a bad time. This is why we spend so much time verifying cash flow assumptions with clients before we rebalance portfolios or invest cash. We believe it is imperative to put a strong defensive foundation in place first—one that protects known cash needs and accounts for unexpected cash needs too—which buys us the time horizon we need for more volatile market segments to perform.

Year-to-Date Performance

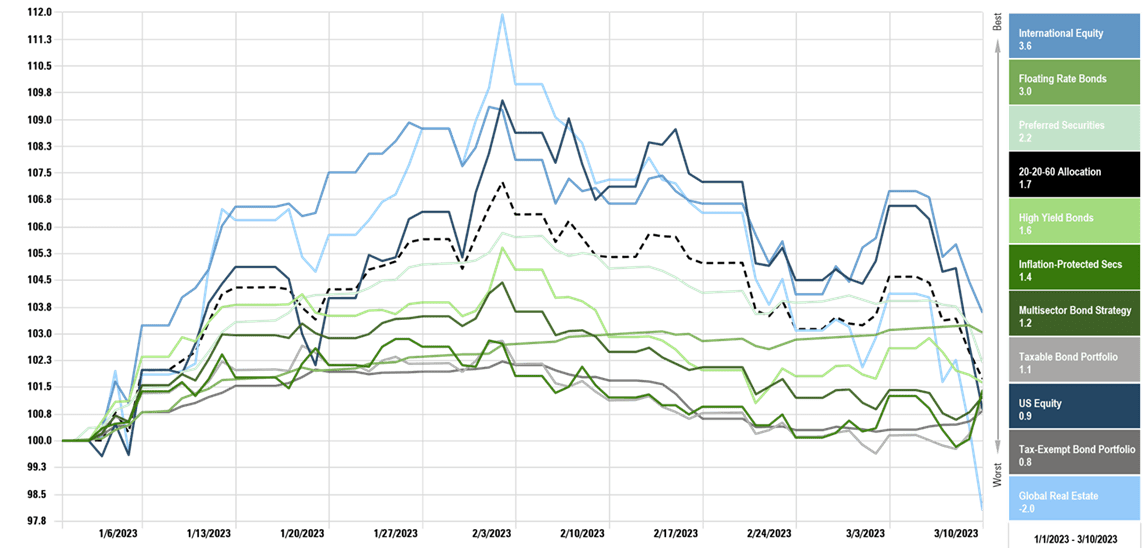

The following chart shows the year-to-date performance for the core market segments within our portfolios.

While every asset class has posted positive returns with the exception of global real estate (as of Friday), it has been a roller coaster throughout the first two and a half months of 2023. Strong returns in January were driven by a continuation of tame inflation readings and renewed hopes the Federal Reserve might pause interest rate hikes sooner than previously expected. But those hopes were squashed in February after a higher-than-expected inflation reading for January along with a particularly strong employment report. Equity and fixed income markets trended lower as investors began to price in a reacceleration of interest rate hikes. As of a week ago, treasury futures were pricing in a strong likelihood of a 50-basis point rate hike next week. But, following the events of the past week, futures are now pricing in a 45% chance of no hike and a 55% chance of a smaller 25-basis point hike following next week’s FOMC meeting (with momentum building for the no hike outcome). It remains to be seen whether a potential pause in rate hikes combined with the swift and decisive actions taken by the government to protect depositors will be enough to put equity and fixed income markets back on an upward trajectory.

In the process we trust

We are not recommending changes to our existing portfolio positioning at this time. Our process for setting client allocations based on the timing and amounts of anticipated cash needs, combined with our belief that portfolios should be broadly diversified among and within asset classes, has enabled us to manage through many periods of heightened volatility and uncertainty before. We believe this time will be no different.

Thank you for being a Brighton Jones client. If you have any questions or concerns, please do not hesitate to reach out to your planning team.